|

|

|

Following our Manassas adventure and the John Brown days at Osawatomie, Kansas, the autumn of 1986 was spent at Pilot Knob, Boonville, and Prairie Grove. The annual Holmes Brigade elections were held at Pilot Knob in which Frank Kirtley was elected to serve in the newly created position of adjutant. At large events, when we formed a battalion, a member from our unit went to serve on the general staff as an administrative flunky handling paperwork and such. Frank was a warrant officer in the Marine Corp and held the position of legal secretary, so he knew a thing or two about paperwork. Second lieutenant's bars came with the job, so for Frank it was like icing on the cake. I retained my rank as 2nd sergeant, Maki 3rd sergeant, and Bill Fannin our 1st sergeant. I gave up my position as Holmes Brigade treasurer and Dan Krueger from St. Louis took over.

March 7-8, 1987 Pea Ridge NMP

The wife and I had visited this park probably ten years earlier during a

vacation in the Ozarks that included a trip to Branson and Wilson's Creek

NMP. It may have been during the summer of '78 that we came to this area

since I was fresh out of Leslie Anders Civil War History class at CMSU and

was finally aware of the Civil War in this region. In 1987, I returned to

Pea Ridge with the Holmes Brigade on an invitation by the park to participate

in the 125th anniversary rededication ceremony. Prior to this, Pea Ridge

NMP had not had any reenactors on their park since the centennial of the

Civil War.

During the time period 1961-1965, the 100th anniversary of the War Between the States was remembered by dedicating new monuments, issuing commemorative stamps, and staging mock battles right on the sacred soil. These early day reenactors ran around in military jump suits, or wore blue jeans and Sears work shirts, with cardboard kepis or cowboy hats atop their heads. BB guns were used as well as M1 Garand rifles firing blanks. In many instances, surplus muskets were used. Yes, actual Civil War weaponry was used; at the time they were cheaper to acquire than a reproduction musket. During the big Centennial battles, there was a certain amount of firing of ramrods from muskets (original ramrods of course), horse manure from artillery, and other forms of lunacy that resulted in a ban by the National Park's Department of all reenactments and reenactors from their battlefield sites.

Twenty-five years later, the NPS still has a ban on reenactments on park property, but they have slowly warmed up to the idea of Living History interpretation. Prior to our visit to Wilson's Creek NMP in 1980 and again in 1983, a few local guys had held a candlelight tour atop Bloody Hill for visitors. These small tableaus were well received by the public and based on the good conduct of those involved, a friendship was made with Park Superintendent Richard Hatcher. Other reenactors were then invited to Wilson's Creek with restrictions on where we could camp, what demonstrations we could do, and how we conducted ourselves. When it became obvious we could behave ourselves at a National Park site, the Wilson's Creek people breathed a sigh of relief, and were instrumental in getting Pea Ridge NMP to allow us in for its rededication ceremony on the 125th anniversary of the battle.

125 years later to the date, Holmes Brigade and Crowley's Clay County Confederates set up camps on the Pea Ridge National Military Park. The Confederates were instructed to set up camp near the visitor center, in what was Brig. Gen. Sam Curtis' headquarters. The Holmes Brigade was allowed to camp near Elkhorn Tavern, approximately one mile north of the Confederate camp. We had a small turnout of Federals, about 25 boys including the "bagladies", but the weather was very agreeable for the first weekend of March. Some speechifying was made by important State politicians, followed by a memorial service complete with a wreath laying, a prayer, and maybe a hymn or two sung. The "johnnies" and us wore black armbands and we had to behave ourselves during this somber moment because we were not only under the watchful eye of the Parks Department, but also under the eye of 1st Sergeant Bill Fannin. Prior to marching out to the ceremony, someone let out a loud fart during roll call. Bill got pissed, because he was afraid that if we started showing any bad behavior-and he'd already warned the "bagladies"-we'd all get kicked out of the park.

Saturday night a candlelight tour was held and was by invitation only. Local bigwigs and other high rolling contributors to the park got to witness scenes of the "battlefield after dark" such as the surgeons operating table in which some poor sap had a "fit" while a bullet was being extracted. Other scenes included soldiers running around in the dark looking for lost comrades, and the ever popular "sit in front of the tent" and play cards, write letters, mend clothes, or gaze blankly at the stars. My role was as Sergeant of the Guard. I'm not sure what I did except probably make a report to the Captain and receive instructions to do something of military importance.

After the tour had concluded later that evening, several of the boys wanted

to go look for ghosts. We were familiar with the stories of ghostly spirits

walking the old battlefields of Antietam and Shiloh and were curious whether

Pea Ridge was also haunted. So about ten of us decided to walk up from Elkhorn

Tavern to the crest of Big Mountain (where the overlook is). We were not

sure what we would find, so we each took our bayonet and trudged up the tour

road. We heard a number of noises, but wasn't sure if it was hoot owls,

wild deer, or the undead. The moon was full and as we neared the top our

eyes began playing tricks on us. Just then we saw a shape at the top but

we couldn't quite make out what it was so we moved to the opposite side of

the road and it appeared to move also. We moved the other way and it moved

as well. At that moment, it seemed a bit closer to us, and it was at that

moment we skedaddled. Back down the hill we trotted, not nearly as quiet

as we'd come up. About halfway down, I felt my bowels began to move, I was

that scared! I veered off the trail and dropped my trousers; ghost or no

ghost I had to evacuate right now! The rest of the gang drew rein alongside

and waited till I'd completed my horrible business, then we continued our

retreat and didn't stop till we'd reached the camp back at Elkhorn. The

next day we went back up to see what had scared us, but it was nothing more

than a metal road sign. What a bunch of old women we'd acted! While at the

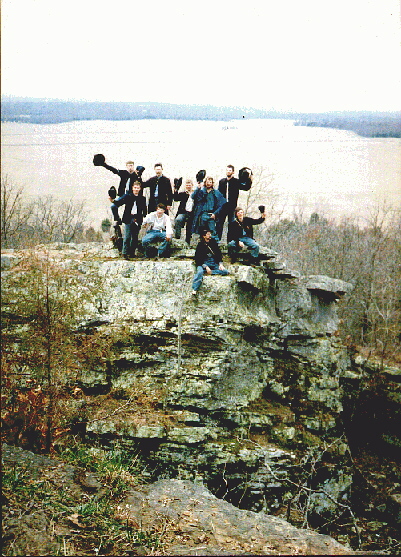

top of Big Mountain Sunday morning, I asked some of the guys to climb up

a twenty-foot tall rock so I could take their picture. The photo I set up

was similar to the Lookout Mountain photo with the boys dangling their legs

over the ledge. The area around Big Mountain reminds one of Devil's Den

in Gettysburg, except the rocks here at Pea Ridge are not as easy to ascend

and could test the patience of a Billy goat. Fortunately, the boys of Holmes

Brigade are part goat themselves, so it wasn't much of a task for them to

reach the top.

After the tour had concluded later that evening, several of the boys wanted

to go look for ghosts. We were familiar with the stories of ghostly spirits

walking the old battlefields of Antietam and Shiloh and were curious whether

Pea Ridge was also haunted. So about ten of us decided to walk up from Elkhorn

Tavern to the crest of Big Mountain (where the overlook is). We were not

sure what we would find, so we each took our bayonet and trudged up the tour

road. We heard a number of noises, but wasn't sure if it was hoot owls,

wild deer, or the undead. The moon was full and as we neared the top our

eyes began playing tricks on us. Just then we saw a shape at the top but

we couldn't quite make out what it was so we moved to the opposite side of

the road and it appeared to move also. We moved the other way and it moved

as well. At that moment, it seemed a bit closer to us, and it was at that

moment we skedaddled. Back down the hill we trotted, not nearly as quiet

as we'd come up. About halfway down, I felt my bowels began to move, I was

that scared! I veered off the trail and dropped my trousers; ghost or no

ghost I had to evacuate right now! The rest of the gang drew rein alongside

and waited till I'd completed my horrible business, then we continued our

retreat and didn't stop till we'd reached the camp back at Elkhorn. The

next day we went back up to see what had scared us, but it was nothing more

than a metal road sign. What a bunch of old women we'd acted! While at the

top of Big Mountain Sunday morning, I asked some of the guys to climb up

a twenty-foot tall rock so I could take their picture. The photo I set up

was similar to the Lookout Mountain photo with the boys dangling their legs

over the ledge. The area around Big Mountain reminds one of Devil's Den

in Gettysburg, except the rocks here at Pea Ridge are not as easy to ascend

and could test the patience of a Billy goat. Fortunately, the boys of Holmes

Brigade are part goat themselves, so it wasn't much of a task for them to

reach the top.

This concluded our visit to Pea Ridge in 1987, but since then we have been invited back a number of times to set up living history encampments as well as take part in commemorations and rededication's at the park. We've developed as fine a relationship with the staff at Pea Ridge as we've enjoyed at Wilson's Creek over the years. Recently, Pea Ridge NMP has allowed us access to former off limits areas including walking the original trench lines near Little Sugar Creek unattended and admittance inside Elkhorn Tavern after hours. They've also given a select few of us the chance to view some of the museum artifacts not on display including Samuel Curtis' Major General's frock coat (which he wears in his late war portrait). Pea Ridge is one of my favorite sites in the Trans-Mississippi and like Wilson's Creek, the terrain remains virtually the same as it appeared over one hundred years ago. Both sites are in the middle of nowhere, have few monuments, and only one modern road running through it for tourists. But they both have an excellent visitor center, an excellent staff, and have developed an excellent working relationship with reenactors and living history interpreters.

April 4-5, 1987 Shiloh, TN.

In the early stages of composing this chapter, I turned to several of my

old pards and asked for their thoughts on Shiloh. What did they remember

most about the 125th anniversary reenactment of April 1987? Their response

was unanimous: COLD! I must admit it was quite a shock to the system

after the mild weather we'd enjoyed one month earlier at Pea Ridge. Once

the sun went down on the Shiloh encampments, the greatcoats came out. I'll

bet the sutlers made money hand over fist selling greatcoats and wool blankets

that weekend. Those that arrived on site early Thursday were treated to

a flurry of light snow, sleet, and bone chilling winds that toppled more

than a few tents. With traffic entering the event site all day Friday-carrying

nearly 6,000 reenactors, horse trailers, artillery, and equipment-the thawing

ground was soon churned up into an ankle deep froth. Vehicles that got stuck,

and there were many, had to pay out the nose for tow service. "The local

good ol' boy seen dollar signs in his eyes as he took his tractor to the

automobile with the out of state license plates." After arriving on Friday

night, there was this civilian who roamed throughout the camp with a couple

of handfuls of straw asking for $4 per handful. It was simply another example

of local profiteering. But the general impression one comes away with about

Shiloh 1987 is that it was the coldest event on record. Two and a half years

later, I would find myself at a much colder event, but that is a tale for

another time.

Early Friday morning April 3rd, about 7 AM, my wife Mona, my 5 year old daughter Katie, and myself left our house in the silver Mitsubishi pickup truck for an eight and a half hour drive from Kansas City to Shiloh. Since the burglary to our home nearly two years earlier, we were reluctant to abandon our home. I think Mona's mother was on a vacation of her own, so the decision was made to hire a house sitter. His name was Tony. He was quiet, intellectual, and attending some college at the time. He looked somewhat like John Condra, the baglady known as the grossest boy in the world. Tony was as mild mannered as an undisturbed pool of bath water. We used Tony at least a half dozen times as a house sitter in the years to come. He always cleaned up after himself. The only knock I had was coming home once after an event and finding several black hairs (pubic?) under the sheets. We always did laundry after he left. Though mild mannered around us, I imagine Tony had a collection of bondage devices in his basement. He was just too damn polite.

We arrived at the event site about 4PM. The reenactment was held

on 600 acres of private land about two miles from the actual battlefield.

We had to register, as all reenactors are wont to do, by signing waivers,

then receiving parking passes, etc. to the camps. The three of us were standing

in one of the half dozen registration lines that stretched outside of a maintenance

building in the Tennessee mud. Mona was talking about something and I was

eyeballing some of the weird characters already dressed out in their uniforms,

when this longhaired fellow with his back to us, turns around.

"Dean Chambre!

Dean was Mona's cousin, ten years her senior. He also grew up in the Fort

Madison/Keokuk Iowa area, had spent many days helping out on the farm with

his relations, then when he became of age; he got a job with the National

Parks Department. Most of his work involved the Forestry Department in such

places as Yellowstone and Glacier Park in Montana. Dean never married and

to this day calls an old Volkswagen van his home. Whenever he'd come to

our home in Independence to visit, he always preferred to sleep in his van

rather than the guestroom. Dean was one of the last wandering nomads. Now

he just happened in be in the same registration line as us at the 125th Shiloh

reenactment.

After the usual hugs and handshakes, he told us he'd only come to visit the site-had neither the desire nor the equipment to reenact. He'd flashed his National Park credentials to gain his admittance and intended to merely wander around the camps, take pictures and then nap in his van. He had hoped to obtain a schedule of activities from this registration line and was literally bowled over by the fact we were here at the exact moment as he. Once we'd signed the proper forms, Dean followed us into the site where we located the spot to pitch our tents.

Mona and Katie would be staying in the 'A' tent, with the two cots, chamber pot, and a half dozen quilts or blankets. Dean helped us with the tent, putting together the two army cots, pulling the wooden boxes from the truck that had the girls clothes and other personal effects in them. Then once the girls seemed content, I drove over to the Federal camp (only a 'quarter mile more')and set up my dog tent. Dean stayed with the girls to chitchat.

As I was setting up the dog tent, the Holmes Brigade boys told me about the previous day's storm. My tent is only two pieces of canvas, roughly 4' high x 6' wide supported by poles. There is no back to my dog tent, so I made sure it was backed up tight against another 'A' tent before I staked it down. I think we had some straw, but it may have been in short supply. By this time the sun was gone and greatcoats, mittens, and scarves came out. Hundreds of campfires from the 600-acre event site were throwing smudges of smoke into the starlit sky. I walked the quarter mile back to the civilian area, passing a number of figures who were huddled over blazing bonfires, some sipping Wild Turkey, some puffing on tobacco, all engaged in conversation of some sort to keep their teeth from chattering. Mona and Katie were getting ready for bed, so I tucked them in under the mound of covers. Dean had left some moments ago to sleep in his van, so I kissed the girl's goodnight and stumbled in the dark back to my dog tent. (I think I moved my truck to the reenactor's parking area the next morning, but I may have done it that night, I don't remember.)

I had the honor of sharing my dog tent with at least 3 other bodies

that Friday and Saturday night. Charlie Pautler, Joe Anderson, and John

Condra all crawled in the dog with me and the combined body heat allowed

us all a 'somewhat ' restful sleep. As I wore everything to bed, even the

greatcoat, mittens and muffler, I had nary a pillow to rest my weary head,

so I rested it on my hardpack. This was a Mexican War issue pack worn on

the back and used to carry extra clothes and personal items. It was composed

of black painted canvas stretched and tacked over a square shaped wooden

frame. I couldn't have done any better if I'd laid my head on a concrete

block.

I had the honor of sharing my dog tent with at least 3 other bodies

that Friday and Saturday night. Charlie Pautler, Joe Anderson, and John

Condra all crawled in the dog with me and the combined body heat allowed

us all a 'somewhat ' restful sleep. As I wore everything to bed, even the

greatcoat, mittens and muffler, I had nary a pillow to rest my weary head,

so I rested it on my hardpack. This was a Mexican War issue pack worn on

the back and used to carry extra clothes and personal items. It was composed

of black painted canvas stretched and tacked over a square shaped wooden

frame. I couldn't have done any better if I'd laid my head on a concrete

block.

The commander of all the Federal troops was again Chris Craft. His goal was that each company should have a strength of 60 men. Holmes Brigade was able to muster two 60-man companies for Shiloh. This included some of our pards from Illinois and Colorado. I was 1st Sergeant of one company, commanded by Dick Stauffer and John Maki was 1st Sergeant of the other, with Don Strother as his captain. The organization was formed into a 'Brigade' with 3 infantry battalions, 5 batteries of artillery, and 75 to 100 cavalry. The Western Battalion or 1st Battalion was composed of the largest number of men at 650 and commanded by Mark Upton. The other two battalions had roughly 200 to 500 men each.

We had brought along our kitchen. We still had not yet learned to go campaign style and eat out of our haversacks. We depended instead on Quartermaster Sergeant Darrell Wilson to take care of us with stew, beans, bacon, and hot biscuits from a Dutch oven. Many of us had started a few years back carrying 'dead things from the sea' or sardines, plus hardtack and jerked beef, but had never tried to cook things ourselves. On a dare, I brought along some PopTarts and Jiffy Pop popcorn. I tried to pop the corn, but I had it to close to the fire and burnt it.

The first thing in the morning after roll call, I hiked over to the civilian camp to check on the girls, and naturally they were still asleep, huddled like little kittens. Katie rolled one little eye out from the cocoon of quilts, but that was all. I gave each a smooch and retied the flaps of the tent as I left. Kathleen Fannin, Connie Soper and some of the other LUAS women were up and about, attending to their morning routine, including the preparation of breakfast. As I started off to rejoin the company, Kathleen and Connie assured me they'd make sure my girls had something to eat and drink. Gail Higginbotham was not at Shiloh; school was still in session and she was hard at work as a teacher back in Missouri. Her husband Gregg rode to the event with Dave Bennett and Chad Dial. During the drive, the young Chad sat in the back seat of the vehicle with radio headphones wrapped around his skull, which made him " look like Max Headroom."

Upon returning to camp, a commotion was going on about all the canteen

water having frozen during the night. Even when a detail tried to draw water

from the US ARMY water buffalo, they came back saying it was mostly all frozen.

As a result, hot coffee had to wait and that's what got the men grumbling.

The boys stood around the fire in bunches, with canteens dangling dangerously

close to the flames. Some canteen covers got charred, but eventually they

had water to brew the coffee bean. In the meantime, the boys all looked

miserable. None had had a good night's sleep, unless it was coaxed with

some alcoholic beverage to warm the blood. Holmes Brigade pard, Jack Williamson

recall's that very cold first morning:

" I remember our chow lines looking like depression era bread lines.

I remember walking into my tent and seeing only a huge mound of clothes.

The mound was quivering. When I lifted a greatcoat flap I found Terry (Forsyth)

saying... oh god...oh god...oh god...it's cold...it's cold...it's cold...

and who drank all the @*?!+*%$# Scotch."

In the light of day, it could be seen that our campsite was a muddy mess. "It was like walking on a waterbed with the moisture below", Jack remembers. " If we stood in line for muster, we slowly sank into the morass below". During infantry drill, the scent of wild onions rose up to the nostrils as a thousand pair of Union brogans smashed the weed underfoot. As we had done at Manassass, the plan of the day for Saturday was to practice infantry tactics. Skirmish drill, changing a battalion front, going by right of companies to the rear into column, forming a division, and the ever popular Grand Review were a few of the tactics we worked on. We may have also learned to "fire by the drum." During the heat of battle, shouted commands cannot always be heard. The "rat-a-tat-tat" of a drum will alert the battalion like a sudden clap of thunder. There is a drum roll to ready the musket, another roll to aim, and then three steady "tat-tat-tat", and then the men pull the triggers. If all the men in the battalion listen, the volley will be crisp and sound as one. Nothing is worse than a man who is late pulling the trigger then does it anyway, about a second late. Speaking of the drum, we also practiced answering the "long roll." While the men are relaxing in camp or even asleep and danger is near, a prolonged drum roll will sound for as long as the drummer can sustain it. The men leap to their feet grabbing musket and accoutrements and dash to their place in line as quickly as possible.

Classic Images Video Production was at Shiloh and as they had done at First Manassass, they hoped to create a documentary/history of the battle by incorporating reenactment footage to tell the story. While both videos used an off camera narrator to tell the story, the Shiloh video added "on camera actors" assuming the roles of high ranking generals who were present during the original battle. Camp Chase Gazette artist Marty Brazil-whom we'd met several years back at Champion's Hill, MS-was a natural for the role of US Grant. Marty had a non-speaking part in which he reviewed a dispatch while chewing a worn out cigar. Another scene that made its way onto the video involved a dialogue between several Generals during a Confederate council of war. An approximate 5-minute debate raged between the men on whether or not to attack the "Yankees!" camped at Shiloh. Some months earlier an advertisement had been held for men who closely resembled the six important Confederate Generals. Acting skills were elementary at best by all participants plus filming was hampered some by helicopters which buzzed the reenactment site throughout the entire weekend, even during the battle on Sunday.

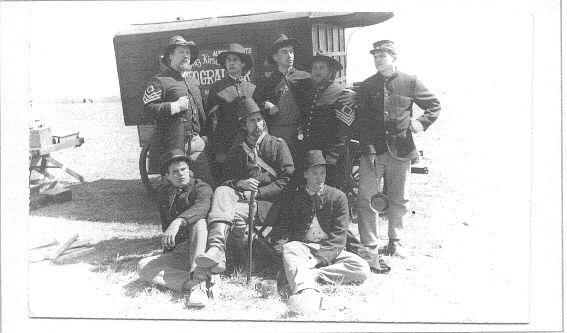

Other than drilling for several hours, we had time on Saturday to visit

photographer Fritz Kirsch who once again was doing CDV images for the boys.

Lieutenant Higginbotham, Sergeants Maki and I-plus some of the bagladies-gathered

for a group photo in which we posed next to the photographer's wagon. In

the evening the Ladies Union Aid Society and a number of the Holmes Brigade

boys, put on a tableau for the entire Western Battalion. A tableau is like

a dramatic play done in acts but the actors do not move. Rather they hold

a position of action while a narrator describes what is taking place. Think

of it as viewing a series of paintings or still photographs with dialogue.

The tableau in question was of a patriotic theme in which two lads march

of to war to preserve Peace, Prosperity, and Liberty. As each scene is presented

to the audience, a story unfolds of battle and death. The "Beast Secession"

is defeated, but one of the lads loses his life. In the final act, the angels

comfort him in death while the narrator tells the audience that his sacrifice

has helped save the Union. What hogwash! But what rousing HUZZAHS were

received at the conclusion of the play from the Western Brigade. Kathleen

and Bill Fannin have been instrumental in bringing these old 19th century

entertainment's back to life. During the late 1980's, the LUAS produced

a couple of different tableaus, usually debuting at Fort Scott. Two of these

tableaus involved that evil killer of men and families: alcohol. I'll have

more to say on tableaus in greater detail in my chapter on Fort Scott.

Other than drilling for several hours, we had time on Saturday to visit

photographer Fritz Kirsch who once again was doing CDV images for the boys.

Lieutenant Higginbotham, Sergeants Maki and I-plus some of the bagladies-gathered

for a group photo in which we posed next to the photographer's wagon. In

the evening the Ladies Union Aid Society and a number of the Holmes Brigade

boys, put on a tableau for the entire Western Battalion. A tableau is like

a dramatic play done in acts but the actors do not move. Rather they hold

a position of action while a narrator describes what is taking place. Think

of it as viewing a series of paintings or still photographs with dialogue.

The tableau in question was of a patriotic theme in which two lads march

of to war to preserve Peace, Prosperity, and Liberty. As each scene is presented

to the audience, a story unfolds of battle and death. The "Beast Secession"

is defeated, but one of the lads loses his life. In the final act, the angels

comfort him in death while the narrator tells the audience that his sacrifice

has helped save the Union. What hogwash! But what rousing HUZZAHS were

received at the conclusion of the play from the Western Brigade. Kathleen

and Bill Fannin have been instrumental in bringing these old 19th century

entertainment's back to life. During the late 1980's, the LUAS produced

a couple of different tableaus, usually debuting at Fort Scott. Two of these

tableaus involved that evil killer of men and families: alcohol. I'll have

more to say on tableaus in greater detail in my chapter on Fort Scott.

At just about the same time as the sun broke Sunday morning, the spectators

began to pour into the site with their lawn chairs, blankets, and coolers,

determined to lay claim to that perfect spot as close to the "battlefield"

as was humanly possible. It didn't matter that the fight wasn't scheduled

till one in the afternoon. Families came to see history recreated and even

if they had to spend three dollars apiece to do it, by God, it was the early

bird who got the worm and that precious piece of real estate close to the

cannon. By 7:30 AM the small two-lane blacktop was already backed up with

traffic and by 11 AM it was bumper to bumper 12 miles in both directions.

The field the battle would be fought on was flat, about three football fields

in length and two in width, with all the spectators packed in on one side.

The sheriff's department estimated the crowd of spectators at 40,000, but

many saw very little of the reenactment. From what I understand, only the

tall people in the first few rows of the mob could see. Little children

sat on Dad's neck while a few brave souls tried a perch in the nearby tree

and mostly ignored the warnings from park rangers to climb down. The rest

would have to make do with what they could hear or what the people up front

felt obligated to comment on in response to inquiries. Where would the Ladies

Union Aid Society members be during this climactic battle reenactment? Would

these fine ladies- who were portraying soldiers wives, mothers, nurses, or

refugees- be cringing in their tents, huddled near the fireplace, clutching

small children in sorrowful embrace while awaiting what fate is dealt to

their dear soldier on the battlefield? Not at all! They had front row seats

to the whole shindig! At each and every event, the authentic civilians (in

particular the soldiers wives and children) are always guaranteed a spot

right in front of everybody. With their blankets and picnic baskets laid

out, the ladies settle back for the grand spectacle, sometimes wave a lace

handkerchief and shout "HUZZAH!" at a familiar soldier as he passes by, and

ignore the bleating from the mob protesting the invasion from these 'civilians'.

The argument that is typically heard is "I got up at the crack of dawn,

drove one whole hour and spent three dollars to be here and now I got reenactment

women sitting in front of me!" Usually when pressed on this issue, one of

the ladies, typically Kathleen Fannin, will calmly put the spectator in his

place by announcing, " My husband and I drove all the way from Missouri

and certainly spent more than three dollars to be here!"

At just about the same time as the sun broke Sunday morning, the spectators

began to pour into the site with their lawn chairs, blankets, and coolers,

determined to lay claim to that perfect spot as close to the "battlefield"

as was humanly possible. It didn't matter that the fight wasn't scheduled

till one in the afternoon. Families came to see history recreated and even

if they had to spend three dollars apiece to do it, by God, it was the early

bird who got the worm and that precious piece of real estate close to the

cannon. By 7:30 AM the small two-lane blacktop was already backed up with

traffic and by 11 AM it was bumper to bumper 12 miles in both directions.

The field the battle would be fought on was flat, about three football fields

in length and two in width, with all the spectators packed in on one side.

The sheriff's department estimated the crowd of spectators at 40,000, but

many saw very little of the reenactment. From what I understand, only the

tall people in the first few rows of the mob could see. Little children

sat on Dad's neck while a few brave souls tried a perch in the nearby tree

and mostly ignored the warnings from park rangers to climb down. The rest

would have to make do with what they could hear or what the people up front

felt obligated to comment on in response to inquiries. Where would the Ladies

Union Aid Society members be during this climactic battle reenactment? Would

these fine ladies- who were portraying soldiers wives, mothers, nurses, or

refugees- be cringing in their tents, huddled near the fireplace, clutching

small children in sorrowful embrace while awaiting what fate is dealt to

their dear soldier on the battlefield? Not at all! They had front row seats

to the whole shindig! At each and every event, the authentic civilians (in

particular the soldiers wives and children) are always guaranteed a spot

right in front of everybody. With their blankets and picnic baskets laid

out, the ladies settle back for the grand spectacle, sometimes wave a lace

handkerchief and shout "HUZZAH!" at a familiar soldier as he passes by, and

ignore the bleating from the mob protesting the invasion from these 'civilians'.

The argument that is typically heard is "I got up at the crack of dawn,

drove one whole hour and spent three dollars to be here and now I got reenactment

women sitting in front of me!" Usually when pressed on this issue, one of

the ladies, typically Kathleen Fannin, will calmly put the spectator in his

place by announcing, " My husband and I drove all the way from Missouri

and certainly spent more than three dollars to be here!"

Like many big scale reenactments, you can only recreate one episode per day. As this reenactment was held on Sunday (Saturday was a day of drill), event sponsors wanted to recreate probably the biggest, fiercest action that took place during the original 1862 battle. And so it was we decided to do the Hornet's Nest fight. This was the fight that occurred on the first day of Shiloh after the Confederates launched their surprise attack. Under heavy pressure, the Federals were being forced to the banks of the Tennessee River and might have been completely annihilated were it not for a small force left along a sunken road to check the rebel advance. This action bought Ulysses S. Grant several precious hours in which to gather reinforcements for a counter attack. But the Union defenders along the area known as the Hornet's Nest paid a bloody price for those precious hours gained.

The battle reenactment began when a skirmish line of 60 men was thrown out from the main Union line to draw the Rebel fire. The men in the skirmish line were in a single rank at intervals of five paces between each man. There was another two companies or 120 men directly behind these in case relief was needed. Finally the bulk of the Federal army was spread out across the width of the field with the artillery guns already in position in the sunken road behind a chest high rail fence. Dozens of individual shots popped from the skirmishers for nearly thirty minutes, these men firing from a prone position to avoid needless loss of life, as they would have been instructed to do even 125 years ago.

After the previously mentioned time had past, the skirmishers were called

in and the entire unit marched off the field to assume places behind the

fence. The whole Federal Brigade was formed in two ranks between the full-scale

artillery guns. I believe there were three or four guns on each end of the

Union line and maybe three more in the center. As this happened way back

in 1987, I'm not sure of the exact placement, but believe this to be about

right.

After the previously mentioned time had past, the skirmishers were called

in and the entire unit marched off the field to assume places behind the

fence. The whole Federal Brigade was formed in two ranks between the full-scale

artillery guns. I believe there were three or four guns on each end of the

Union line and maybe three more in the center. As this happened way back

in 1987, I'm not sure of the exact placement, but believe this to be about

right.

Once the Infantry had cleared the field, the artillery boys opened up with their own symphony of noise and smoke against the rebel guns, which were spread out on the distant bluff. In an instant and probably lasting another whole half-hour, a fierce bombardment rained down upon us. Ground charges had been planted all up and down the line, just on the other side of the fence. Wires from these ground charges ran back to several battery powered juncture boxes and at a prearranged signal, and in conjunction with the firing of rebel cannon, a wire was touched against a metal rod, with the result being one of these ground charges went off. I think they must have used a whole pound of black powder to each charge, because it was a deafening blast with loose soil hurled sky ward or tossed back upon us Federal infantry soldiers who could only hug the ground while the dirt clods bounced off our heads. Also a number of airbursts cracked over us as well. These came from a mortar that was concealed in the woods out of sight of the public. I think the wind was blowing in our faces this day, so we had the smoke from our own artillery guns washing over us as well. (Note: I think old pard Steve Lillard was in charge of the pyro/fireworks for this event. How he got involved in this facet of reenactment I'll never know. Could it be something he learned as a result of the Roscoe, MO event of '84? Steve would continue on at a number of MCWRA events as head coordination of ground/aerial explosions.)

As First Sergeant, my position was five paces to the rear of the line. The battalion was pressed up against the fence with some boys blazing away with their muskets, while a few lads began digging foxholes with their bayonets trying to escape the madness of the barrage. Joe Anderson and Charlie Pautler were among those trying to dig their way to China. The battalion officers and NCO's walked up and down the line with words of encouragement, including Captain Dick who came past many times, with a fatherly word or a slight touch to the trembling shoulder of a young lad. I did my turn as well, usually with a peck on the cheek to one of the bagladies. During one close ground explosion, a clod of dirt about the size of a softball struck me. I went into an act that I thought surely would win me an Academy Award nomination, but after an examination by a surgeon, he declared it only a minor annoyance and I was restored to active duty.

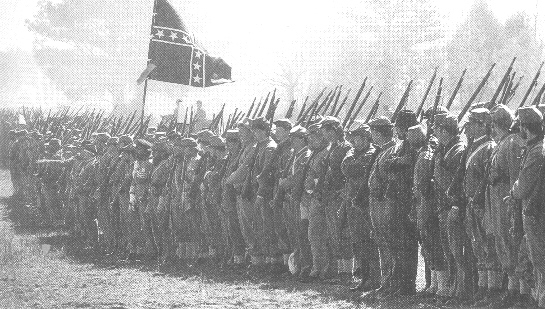

About a half-hour after it started, the artillery fire slackened and

a cheer went up from forty thousand throats as the spectators welcomed the

arrival of the Rebel horde. They'd materialized from the haze of gun smoke,

a distance of several hundred yards away, with their line of battle at least

a quarter-mile long. With the exception of a slouch hat or two and a few

butternut jackets, you'd think you were looking at the bloody Army of Northern

Virginia. Most of these Rebels, who should have had more of a western look

in appearance, wore gray uniforms and forage caps, with a good number sporting

the ever-popular canvas gaiters around their ankles. With the popular British

Enfield in their grip, the gray clad soldiers inched their way down like

a slow moving tidal wave. The Confederate guns were silent while their comrades

passed through, but the cannoneers themselves cheered, tipped their hats

in salute, and shouted words of encouragement to the steadfast marchers on

their way to the Hornet's Nest.

About a half-hour after it started, the artillery fire slackened and

a cheer went up from forty thousand throats as the spectators welcomed the

arrival of the Rebel horde. They'd materialized from the haze of gun smoke,

a distance of several hundred yards away, with their line of battle at least

a quarter-mile long. With the exception of a slouch hat or two and a few

butternut jackets, you'd think you were looking at the bloody Army of Northern

Virginia. Most of these Rebels, who should have had more of a western look

in appearance, wore gray uniforms and forage caps, with a good number sporting

the ever-popular canvas gaiters around their ankles. With the popular British

Enfield in their grip, the gray clad soldiers inched their way down like

a slow moving tidal wave. The Confederate guns were silent while their comrades

passed through, but the cannoneers themselves cheered, tipped their hats

in salute, and shouted words of encouragement to the steadfast marchers on

their way to the Hornet's Nest.

The battle scenario called for the rebel army to make three (3) charges against the Federal works. Each attack would result in a number of fatalities as suggested by the battalion commander, but typically the men decided their own fate. For example, a commander might say, "Ok, in this attack, we need x number of men to fall here, then a few more to fall during this phase of the battle, with even more to fall during the retreat. But not every man that falls has to be killed. Some can be slightly wounded, others severely. If you run out of ammo, you can take a hit, etc." These are all suggestions, but mostly it is left up to the individual when he wants to fall, or if he wants to. In some reenactments, a man draws a slip of paper prior to the commencement of the battle. Each slip will tell the man if he is wounded, killed, or escapes injury all together. With all these good intentions and suggestions, the major determining factor in deciding if you want to take a hit is: how tired am I, can I make my wounding/death look good, do I want to blow any more cartridges, or have I run out of cartridges? With these questions festering in their peanut brains, the men of the Rebel army halted at a distance of two hundred yards from our works and began letting loose with ragged volleys.

Our ears were still ringing from the cannons and the ground explosions, when the command was given to fire at will. The lads in blue jockeyed for position along the rail fence, some standing, some at a crouch with the musket barrel poked out from between the rails. The entire fence line, stretching almost a quarter mile, erupted all up and down with flame as the muskets spoke. During the infantry portion of the battle, it was remembered that, "Don Whitson had some monsters for his musket (usually 120 grains of black powder in a cartridge rather than the prescribed 60 grains), and every time he fired, the guys around him would cuss him out." Also, it was noted that "Some yahoos caught and killed a chicken so they could smear real blood on themselves." It looked good for a while, but began to stink and draw flies. A few rebel scarecrows began to take hits, staggering out of line or falling where they stood. Rebel officers on horseback could be seen riding among the men, shouting words of encouragement, some waving swords in the air.

This exchange of small arms occupied the space of maybe fifteen minutes, when, with a shout, the ragged Rebel line advanced at a walk. "He comes the first of three charges," I mused thinking this reenactment would be fought like the one fought in Pilot Knob, Missouri in which the Confederates charged the earthworks three times during the September 1864 battle. As the Rebs got to within 100 yards and they changed from a walk to a trot, I began to get an inkling something wasn't quite right. I thought, surely, the Reb commander would halt them once they got within 50 yards, turn them around, and fall back to the rear to reorganize for the second charge. Much to my surprise, unit cohesion in the Rebel line suddenly evaporated as these scarecrows broke into a dead run, becoming less an army than a mob. At about the same time, I happened to notice an activity on our left that made my blood go cold. A battalion of Confederate infantrymen had flanked us, and was working their way to our rear. They had accomplished this brazen act by running through the area occupied by the audience. I'm sure it was very thrilling to the crowd to see armed men run past them only inches away from their faces. Fortunately, no one was struck by a swinging musket or had his or her toes stepped on as the Rebel scarecrows burst through.

"Captain, we're flanked!" I recall shouting to Dick. He glanced to his left, where the activity was taking place some yards from us, then he turned back around to face me with a grim look of exasperation and resignation. His shoulder sagged a bit as he sadly realized, as I did, that the scenario had been broken. After only one charge, the battle reenactment was over. Colonel Craft was withdrawing men from the left to cover this newest disaster to our flank, but it was all in vain. Meanwhile, the main Rebel line was upon us and was ripping down the rail fence like angry beavers. Nothing could be gained now except to try to save ourselves or surrender. Jack Williamson remembered, "when them Rebs cracked our line and looking back for my pard Terry. He had 4 Rebs on his back and was slapping at them like mosquitoes.

Even as we were breaking ranks, the crowd of 40,000 was breaking ranks also. Not content to allow the reenactment to come to a natural conclusion, they joined the confusion toward the Union camps, or their cars, in most cases getting in the middle of soldiers both Blue and Gray. "Please let us finish it (the reenactment) the way we want to," one Shiloh Reenactment Association member pleaded with the civilian mob as barricades were pushed aside. "Please hold back. The soldiers are supposed to surround the Hornet's Nest; not the spectators!" Another reenactment official said it this way: " The crowd broke through before the last phase of the battle was fought, and it had to be stopped before it was completely over." At the conclusion of some reenactments, a bugler will play "Taps" in remembrance of all the men who fell during the original battle. During this somber time, soldiers of both the Blue and Gray will remove their hats for a moment of silence, then the two sides will sometimes shake hands and pat each other on the back and say, "Good show, old man!" There was no chance given for such a ceremony this day. Instead of a moment of silence to honor the dead, the 125th anniversary reenactment of Shiloh event fizzled out like a sputtering fuse as the spectators took the field.

After many years had passed, I received a letter from ex-newsletter

editor and good friend, Dave Bennett, who during the 1987 event was a Brigade

commander with the Confederate Army. When I told him I wished to write about

the incidents of Shiloh and in particular the "flanking by the Rebs", he

had this to say:

"The whole thing about the Confederates flanking the Federals, I know

a little how it all came about. During a meeting many months before the

event, Brigade commanders, Federal and Confederate were all walking the battlefield.

I do not remember his name, but the overall Federal commander (Chris

Craft?) was boasting to everyone that not one Federal soldier would surrender

in the Hornets Nest. His plan was to move everyone out and therefore no

prisoners would be had. Of course, this was not consistent with the Historical

Fact. This really put (Confederate Army commander John L.) Weaver's

short hairs in a tizzy. As we stood on a ridge.....he asked me what I thought

of the tactical situation. I responded that the Confederate right or Federal

left was right up against a wooded tree line that was fenced. Only on the

Federal right would the field allow a flanking movement, and therefore, that

is where the Federals would be expecting us to turn their flank. With that,

Weaver then planned his big surprise. During the battle, my brigade of

850 plus infantry, was supplemented with the Confederate Cavalry and horse

artillery. I was to make a big demonstration as if I was going to turn

the flank. Plus, during the battle, I shifted my Infantry Battalions to

my right. The center Brigade did the same thing, and Jack King of the far

right Brigade pulled a Battalion off the line, and they snuck through the

woods on their right to come out in the rear of the Hornets nest. None

of that would happen if the little Federal General was not a braggart. The

Confederate commander also had an ego as long as the Missouri River and the

two were constantly sparring."

So concludes my brief narrative on the 125th anniversary of Shiloh. It may not have seemed much to the reader. It did not seem much of an event to me, to be honest. Other than the above-mentioned incidents, there isn't much else to write about. By the time I broke down both tents, packed up the Mitsubishi, and made it out of the event site some hours later, the girls and I decided to spend the night in a motel near Memphis. I had not slept that well during the chill of both nights, plus I had Monday off work. For little five year old Katie, it was her first experience in a motel and she was excited with wide-eyed enthusiasm. We had a bite to eat and I fell asleep as soon as we came back to the room and I hit the pillow.

Chapter Thirty: Lone Jack and Rattlesnake Dick